New Brain Research Seeks to Understand the Nature of Cravings

In the midst of a discussion with Dr. Owen Carmichael on the texture of melted chocolate or the color and hue of a fresh batch of French fries, you might guess that he is a chef or a food critic. As cool as those jobs are, those guesses don't come close. Take his fascination with food and mix in a heavy dose of the biomedical sciences to find the answer. Dr. Carmichael is a brain scientist at LSU's Pennington Biomedical Research Center, and he is striving to understand the way cravings, such as those we have for food, are embodied.

Some of us may brush off cravings as a normal aspect of our personalities, but Carmichael reveals that overwhelming cravings are a very real problem often found at the center of weight struggles and obesity – struggles that can lead to diabetes, high blood pressure and a host of other health problems.

"We think that becoming overweight could change the brain, and people who are obese may have a heightened sensitivity to certain attributes such as the sweetness of food," said Carmichael. "We want to know how to combat these cravings."

The first step to combatting cravings is in understanding how the brain processes food information, something Carmichael is doing now with the help of volunteers from the community.

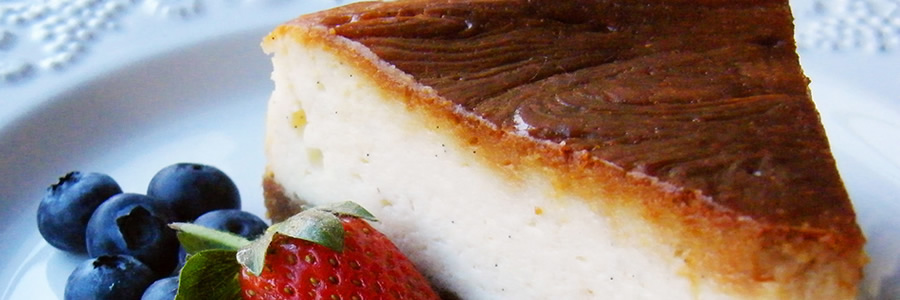

Carmichael and researchers at Pennington Biomedical have put a together a catalog of different food images ranging from high fat and sugary foods to those that are much healthier.

Carmichael asked volunteers to undergo an MRI while his team showed them the food photos. They asked volunteers several questions: Is this food delicious or is it disgusting? Do you eat this food or do you not eat this food? How interesting is this photo?

While each volunteer saw food images appearing, the MRI was scanning their brain to show which area lit up in response to each photo.

"We see different parts of the brain light up when we are shown foods that taste really good to us such as indulgent dishes, than we do when we are shown foods that we know are ‘good for us,'" said Carmichael. "The reward circuit uses past experience to value a stimulus, like a skinless chicken breast for example. Sure, chicken breasts can be flavorful but there is not a lot of pleasure associated with them. Looking at cheesecake, on the other hand, will turn on that reward circuit, thanks to its sweetness and taste."

Armed with that information, Carmichael is able to better understand the reward circuit in our brains, which could eventually lead to better weight management therapies and to a better understanding of weight loss – something vitally important, given the increasing rate of obesity in Louisiana and around the world.

Carmichael hopes to amp up this work in the future by not only showing volunteers photos of food, but by asking them to taste foods while in the MRI.

"Adding taste response to visual response could give us information about how the brain starts to crave desirable foods in the first place. Eventually we may be able to test the feasibility of medications that suppress cravings by collecting MRI data before and after volunteers take those medications," said Carmichael.

"This is all a part of our effort to help people live longer, healthier lives," said Carmichael, "One day those New Year's resolutions to eat better and lose weight may be a little easier to keep thanks to scientific research and innovations from Pennington Biomedical right here in Baton Rouge."

For more information on how you can support this and other projects at LSU’s Pennington Biomedical Research Center, visit www.pbrf.org.